The article explains the significant growth of the private debt market and outlines the accounting valuation methods under HGB and IFRS 9, which primarily rely on discounting future cash flows and recognizing expected credit losses. It then details the unique valuation challenges across different private debt segments—like direct lending, real estate, and mezzanine financing—which stem from their illiquidity and necessitate complex, model-based fair value measurements.

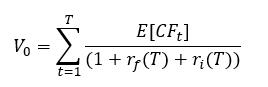

In the last two decades, the volume of private debt loans in the USA has risen from around USD 45 billion to around USD 1 trillion (Fillat et al., 2025). Since the 2007/2008 financial crisis, banks have been subject to stricter regulations for accounting for loans (e.g. Basel III, MaRsik or special minimum depreciation). However, private debt loans have also been subject to stricter regulations under IFRS and HGB since the financial crisis. IFRS 9 deals with the classification, measurement and impairment of all financial instruments and therefore also applies to private debt loans. For the valuation of loans, the present value is determined by discounting future payment flows over the term. The discount rate, which is made up of the risk-free interest rate, which reflects the "remuneration" over time, and a risk premium, which represents the "remuneration" for the risk assumed, is decisive for the correct valuation. In general, the present value can be expressed as:

Where R[CFt] is the expected cash flow at the time t, rf (T) is the risk-free rate and ri (T) is the risk premium depending on the term T. The effective interest rate describes an interest rate at which all contractually agreed future payment flows (interest, amortisation, premium, discount, fees, etc.) are distributed as a constant periodic interest rate over the entire term.

In practice, the valuation of loans is required for accounting in accordance with IFRS 9, transactions or internal risk analyses and portfolio management.

Valuation in accordance with HGB is generally based on the principle of prudence (§ 252 (1) no. 4). Receivables from loans are recognised at cost (less any discount). Subsequent measurement is at amortised cost, i.e. nominal amount less repayments already made. Fixed asset receivables must be amortized to the lower fair value in the event of permanent impairment. (§ 253 (3) HGB). Current assets must be amortized to their lower fair value even in the event of a temporary impairment. (§ 253 (4) HGB). If the reasons for the impairment no longer exist, a write-up (to a maximum of amortised cost) must be made (§ 253 (5) HGB).

Liabilities from loans are recognised at the settlement amount (§ 253 (1) HGB). If the settlement amount is higher than the issue amount (discount), the difference may be recognised as prepaid expenses and is amortised over the scheduled term of the liability (§ 250 (3) HGB).

In accordance with IFRS 9, both receivables and liabilities are initially recognised at fair value (IFRS 9 5.1.1). Subsequent measurement is generally at amortised cost using the effective interest method (IFRS 9 5.2.1-5.2.3, 5.3.1-5.3.2 & 5.4.1). In addition, expected credit losses (ECL) must be recognised from the date of initial recognition (IFRS 9 5.5.1-5.5.7). Reversals of impairment losses due to decreasing default risks must be recognised in profit or loss, as must deteriorations (IFRS 9 5.5.8). Only if receivables are classified at fair value through profit or loss (FVTPL) or fair value through other comprehensive income (FVOCI) (IFRS 9 5.2.1) does subsequent measurement at fair value apply instead of effective interest measurement. This is determined in accordance with the requirements of IFRS 13, which specifies a hierarchy of inputs: Level 1 (quoted market prices), Level 2 (observable inputs, e.g. yield curves or credit spreads) and Level 3 (unobservable inputs, typically model-based cash flow discounting methods). Particularly in the area of private debt, where active market prices are regularly lacking, measurement is performed almost exclusively on a Level 3 basis, with disclosure of the underlying assumptions and sensitivities (IFRS 13 72-90).

Private debt refers to loans that are granted directly to companies by non-bank investors outside the traditional banking system and without being placed on the capital market. Private debt investors are typically institutional investors such as insurance companies, family offices or specialized private debt funds. Private debt loans are typically granted bilaterally or in small syndicates. They are usually uncertificated, illiquid and negotiated directly, which allows for flexibility in terms of maturity, collateralization and seniority. This results in several advantages of private debt financing compared to traditional bank financing. Private debt funds are not bound by the same capital backing requirements as banks and can therefore offer more flexible forms of credit (e.g. mezzanine, venture debt, etc.). In addition, they can generally make faster decisions and take higher risks. Frequent areas of application are buyouts (LBA/MBO), turnarounds, distressed cases or growth companies.

Direct lending, also known as the "classic" form of private debt, are usually senior secured loans with medium terms (5-7 years) and variable floating rates. They are mostly granted to medium-sized companies for refinancing or growth financing, often as part of LBOs or MBOs.

Valuation challenges:

As direct lending loans are illiquid and there are usually no active secondary markets, a mark-to-market valuation is rarely possible. The valuation is based exclusively on internal fund cash flow models. Medium-sized companies generally do not have a credit rating, which is why risk calculations must also be carried out internally.

This segment comprises private loans to finance real estate projects or portfolios. Real estate debt can include both development-related financing (e.g. construction loans, project development financing) and portfolio financing (e.g. mortgage loans for commercial real estate) granted by non-banks.

Valuation challenges:

Although there are market values (appraisals) for real estate itself, the loan valuation requires an assessment of the loan-to-value and the project risks. Illiquidity is also a problem with real estate loans, as these are rarely traded. The fair value depends heavily on the current market situation on the real estate market (rent levels, vacancy rates, capitalization interest rates). The interest rate turnaround in 2022/23 in particular has put property values under pressure and thus weakened the collateralization of many loans. In addition, real estate loans are idiosyncratic, i.e. each financing is structured individually (location of the property, project progress, tenant creditworthiness, etc.), which makes standardized valuation approaches difficult.

These are loans to finance infrastructure projects or operators, such as energy generation plants (wind/solar parks), supply networks, transport infrastructure (roads, airports) or telecommunications facilities. Infrastructure loans are characterized by very long terms, often 20 to over 30 years, in line with the long useful life of the facilities. Due to the long terms, the payments can be inflation-indexed to ensure stable real returns. There are often government purchase guarantees or regulated revenue models, which reduces the risk of default; accordingly, core infrastructure loans are considered relatively safe with ratings in the investment grade range. However, private infrastructure debt funds also finance projects with non-recourse or limited recourse. In the case of a non-recourse loan, the loan is limited exclusively to the cash flows and collateral of the financed project. If the income from the project is not sufficient to service the loan, the lender cannot draw on the parent company's assets. Limited recourse is a hybrid form in which certain guarantees are granted.

Valuation challenges:

The long terms make the valuation sensitive to changes in interest rates. As infrastructure projects are often unique, there is hardly any market comparison data. The valuation is therefore based on cash flow models of the respective project, which must take into account construction costs, operating costs, capacity utilization, regulatory fees, etc. Macroeconomic risks (e.g. changes in regulation, technological changes, interest rate changes, etc.) must be taken into account with risk premiums. In addition, many infrastructure loans are illiquid, meaning that there are generally no observable market prices or input factors for their measurement. Under IFRS 13, they are therefore regularly recognized as Level 3 instruments.

This segment comprises investments in loans to companies in financial distress. These include, for example, non-performing loans (NPLs) purchased from banks on the secondary market as well as newly granted rescue or restructuring loans to companies in financial distress. A distinction is made between stressed debt, loans from companies that have problems but have not yet defaulted, and distressed debt in the narrower sense, where there are already payment defaults and a proximity to insolvency.

Valuation challenges:

The valuation of non-performing loans is uncertain as it is based on assumptions as to how much of the loan can be serviced. This depends on the successful restructuring of the debtor or the realization of collateral. IFRS also requires special effective interest calculations for purchased or originated credit-impaired loans (POCI) and always lifetime ECLs. In practice, distressed loans are often valued at a market price based on the most recent transactions, if such values are available at all.

Mezzanine capital is a hybrid of debt and equity. It is often used when a company is already heavily indebted and therefore needs to rely more on equity financing, preferably without giving up voting rights. Mezzanine financing typically consists of a fixed-interest subordinated loan combined with a profit or performance-related component (e.g. option rights to company shares or profit participation). They are contractually subordinated to all senior liabilities and interest payments are often deferred (PIK - Pay in Kind interest or bullet bonus interest) to give the company more liquidity headroom. As compensation for the higher risk, a higher coupon interest rate is usually agreed. In addition, the mezzanine lender participates in the company's success through option rights or profit sharing. In some cases, mezzanine capital can be presented as equity in the balance sheet, for example as silent partnerships or perpetual loans with subordination and profit participation. This enables a combination with traditional bank loans. If the bank requires a certain debt limit, a mezzanine donor can help to reduce the debt ratio, making the bank loan possible.

Valuation challenges:

Mezzanine financing is challenging in terms of accounting and economics because it combines elements of debt and equity. The valuation usually requires a separation of the components: The loan component is treated as a subordinated debt instrument and is subject to a correspondingly high credit spread due to the increased default risk. Embedded equity options, such as profit-sharing or conversion rights, on the other hand, must be measured using financial mathematical methods, typically option pricing models. In such cases, IFRS 9 provides for a split into separate derivatives and liability components, with the derivatives being measured at fair value and the liability components at amortized cost. Subordination increases sensitivity to deterioration in the company's position. Even moderate stress scenarios can significantly reduce the value of the mezzanine position, as a total default is possible at any time. At the same time, the equity component opens up disproportionate participation in positive company developments. This asymmetrical risk-return profile makes scenario analyses essential. As there are rarely liquid markets for mezzanine financing in practice, the valuation is predominantly carried out as a Level 3 measurement in accordance with IFRS 13, based on discounted cash flows with risk-adequate discount rates in combination with option valuations.

Venture debt refers to loans that are granted to start-ups or young, growth companies, typically in addition to venture capital. Venture debt lenders provide relatively short-term loans (often 1-3 years), e.g. to bridge the gap until the next equity round or to accelerate growth between two VC rounds. The loans are unsecured or only weakly secured, as start-ups rarely have material collateral. Convertible elements or option rights are typical. Venture debt providers almost always receive warrant options on shares in the company in order to participate in its success or it is agreed that the loan can be converted into equity in the event of failure. The coupon interest rate is usually higher and partly deferred to compensate for the increased default risk.

Valuation challenges:

Venture loans are at the interface with equity capital, as the probability of total default is high, but at the same time there is enormous upside potential in the event of success, through equity participation via options or convertible elements. In practice, the debt components are valued using discounted cash flow models (DCF) with high risk premiums, while the embedded options are valued using financial mathematical methods such as binomial or Black-Scholes models. As there are usually no liquid markets for venture debt, the valuation is almost always carried out as a Level 3 measurement in accordance with IFRS 13.

Fillat, J. L., Landoni, M., Levin, J. D., & Wang, J. C. (2025, May 21). Could the growth of private credit pose a risk to financial system stability? Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, Current Policy Perspectives, 25-8. https://www.bostonfed.org/publications/current-policy-perspectives/2025/could-the-growth-of-private-credit-pose-a-risk-to-financial-system-stability.aspx

We support you in researching the data — e.g. putting together the peer group — with a short training session on how to use the platform. We are happy to do this based on your specific project.